Dynamics of Russia’s position in democracy and freedom indices: research and approaches to explanation

Mark Ivanov, a first-year student/School of Governance and Politics

Abstract

The core goal of the study is to identify tendencies of Russia’s development in the medium term. Using almost 2 decades of data of eight indices, I examine Russia’s position and its dynamics through the years. The article takes into account both political and non-political indices of conditions of a state. The changes of Russia’s position that happened in last 2 decades were analyzed, described, estimated, and converted into easily perceived graphs. The article also presents three different explanations of study’s results. By analyzing the results, I try to reveal correlations of the country’s position between democracy and non-political rankings.

Key words: measuring democracy, democracy indices, Russia, democracy vs. autocracy, index correlation, current Russian policy.

Despite the long theoretical tradition and broad increase in democratic states, the interest in practical comparison studies has been aroused only relatively recently. The first methodological developments in comparative analysis of different democratic regimes were used in the 1970s and 1980s in such projects as “Polity”, “Freedom in the World” and a number of projects of Helsinki University under the direction of Tatu Vanhanen.

Today’s the most popular regularly updated democracy rankings are The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, Bertelsmann Transformation Index, The Democracy Ranking, and two ratings of “Freedom House”: Nations in Transit and Freedom in the World. In such research projects, variables representing various criterion of democratic development are aggregated in complex indices that aim to measure an overall level of democracy. It is up to index compilers what to choose. They can either use a range of criteria to get a more complete picture or focus on a few criteria to facilitate measuring on a regular basis – at least once per two years. In the present case, it is impossible to combine, due to limited resources and a global level of a research. It is of significant importance to dynamically show a country’s position especially for states in transit or young democracies like Russia, for instance. Deep and thorough research projects like “Political Atlas of the Modern World”, which cover a massive number of quantitative characteristics, give only a cross section of a particular year. They quickly become obsolete and in a few years they are unsuitable for use in comparative analysis. For example, “Political Atlas of the Modern World” was created in 2008 and now it is objectively not relevant to the present day. For example, the Atlas ranks Ukraine above Latvia and Estonia, Georgia below Uzbekistan. Obviously, such comparisons are outdated.

This article helps to identify directions of political and non-political development of Russia. I examined four democracy indices and four non-political indices assessing economic, information, business, and moral spaces of Russia. The comparison of them shows paradoxical, though accurate, results. Part one of this study shows the obtained results and their description. The second part presents different practical approaches to their explanation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

At first, I need to show the dynamics of Russia in indices, which focus on progressive trends of global societal development. Democratization, consolidating stability of democratic institutions, promoting openness of an electoral processes, improving the quality of management, strengthening of guarantees of mass media and business’s freedom, as well as an expansion of moral freedom are core factors promoted and defended by industrially developed western nations. As we can see, almost all of them are political. First, I examine indices of political aspects that are measured by democracy indices.

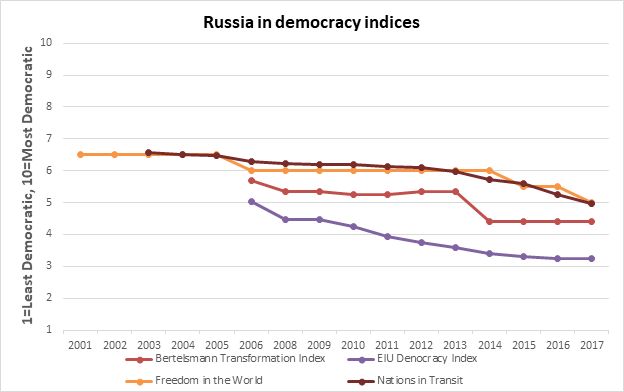

Figure 1. Russia in democracy indices.

It shows a sharply negative tendency of Russia’s political development. All presented rankings classify current Russian political regime as “Not Free,” “Authoritarian,” “Moderate Autocracy,” or “Consolidated Authoritarian Regime”. Although they cannot agree on when that political fracture happened. According to Democracy Index (The Economist Intelligence Unit) and Nations in Transit Index (Freedom House), it is the period of 2009-2010 years. However, Freedom in the World Index (Freedom House) and Bertelsmann Transformation Index (Bertelsmann Stiftung) points at 2005 and 2014 respectively.

For my research, all of the indices used share a common liberal democratic origin. Based on that fact I can assume that they have similar political positions in both political and other spheres.

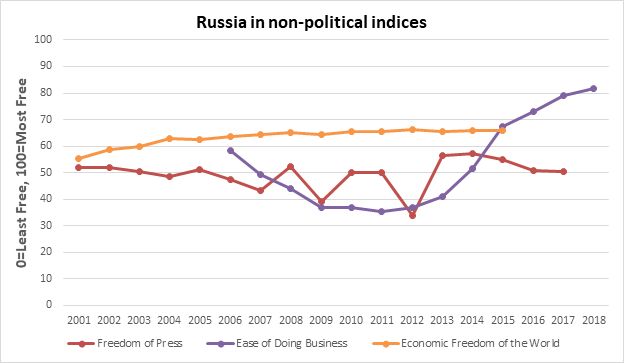

Figure 2. Russia in non-political indices.

Surprisingly, the obtained results completely do not agree with the assumption. These rankings show opposite to previous indices’ results. They are not sharply positive but still the dynamics is obviously reassuring.

We can see the movement towards expansion of freedom in economic and business sphere. We can’t see the same in Freedom of Press Index, but still, even in the partly politicized Freedom House’s Index the positions of Russia changed from highly unfree years, which are shown in the graph by the dips of the line, to stable positions. In the World Index of Moral Freedom Russia ranked fifty-third, ahead of such “Full Democracies” as Lithuania, Romania, Poland, and Japan.

The presented results mean that different aspects of Russia develop in opposite vectors. One can say that there is an example of China that shows the liberalization of economics within an authoritarian power structure is possible. I suppose that this is not the case in Russia because I examined indices not only of economics but culture, business, and mass media. I think that it is quite enough to say that elements of liberal democracy are widely visible in Russia in each and every sphere.

In the informational space of Russia, there are these approaches to explaining of that paradox.

The political opposition concept states that there is a process of “rooting” of current political elite in Russia. They caused the government to impose direct or physical controls and consciously prevent the development of democratic institution to be in power as long as they can.

Representatives of the authority say that there is a correlation between the movement towards greater independence in the international area and “independent” expert evaluation. The West uses these indices to justify influencing Russia.

There is another way of explaining the paradox. Politically neutral experts are of the opinion that after 1990’s the necessary process of society cohesion was implemented by the use of force and restriction of some civic and political rights due to the lack of a qualitatively different public administration experience.

References:

1. Melville, A. (2009) “Political Atlas of the Modern World: An Experiment in Multidimensional Statistical Analysis of the Political Systems of Modern States.” MGIMO — University Press.

2. Vanhanen, T. (1984) “The emergence of democracy: A comparative study of 119 states, 1850-1979.” Societas scientiarum fennica.

3. Vanhanen, T. (1997) “Prospects of democracy: A study of 172 countries.” Routledge.

4. Huntington, S.P. (1991) “The Third Wave. Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century.” Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press.

5. Tokarev, A. A. (2014) “Democracy ratings: from bias to science.” Perspectives and prospects.

6. Brusis, M., Siegmund, J. (2012) “Sustainable Governance Indicators 2011. Concepts and Methodology.” Sustainable Governance in BRICS.

7. Welzel, C. & A. Alexander (2008). “Measuring Effective Democracy: The Human Empowerment Approach.” World Values Research.

8. Dahl, R. A. (1999) “On Democracy.” New Haven: Yale University Press.